Author: Esther Hamilton

Less famous than other Kentish Airfields such as RAF Biggin Hill (of 1940’s Battle of Britain), RAF Ashford was, a hub of activity for a few short years in the final years of the Second World War. One of the new Advanced Landing Grounds (ALGs) built after 1942, it was a key part of the linear constellation of airfields, made up of (to name but a few) those at Woodchurch, Staplehurst, High Halden, Kingsnorth and Lashenden that dotted the Kentish landscape between Biggin Hill and the continent.[i]

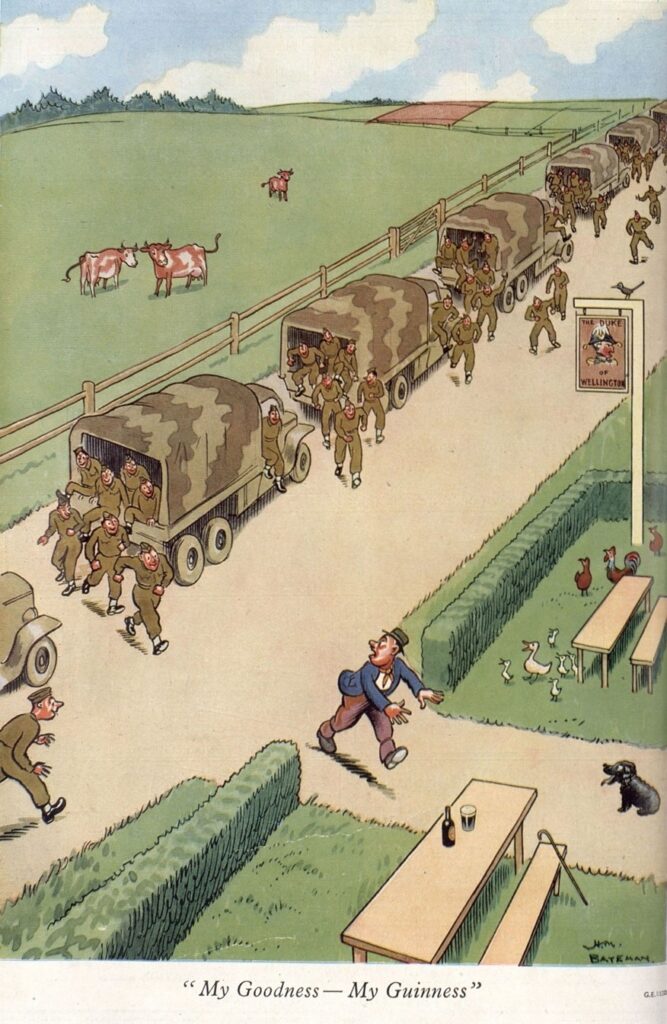

Opened for use on the 13th of April 1943, the site was first occupied by the 65th and 122nd and their Spitfires but was last used by the USAAF’s 406th Flight Group, in July 1944 before the airfield’s land was derequisitioned. What did the local population think about this? We can tell from popular media of the time, such as this Guiness advert, that rural communities feared yet expected that their property would be seized for use by the military.

[i] Brooks, R. J. (1998) Kent Airfields in the Second World War.

At Chilmington, Singleton Manor, once home to the famous Elizabeth Quinton Strouts, military men were permitted full use of the property, and even decades later, their used tins of boot polish and match boxes were being uncovered beneath the manor’s floorboards.

We may hear later on in the project, after collecting local oral histories, about how RAF Ashford’s presence affected the small local communities of the village of Great Chart and the hamlet of Chilmington.

But what was life like for the men that found themselves as this newly built airstrip? Although brief, RAF Ashford’s existence was more than as a strategic spot on the map: it was a place where men shaved in the mud, brewed coffee in makeshift cafes, and lived out their war service in one damp tent and boot polish tin at a time.

RCAF

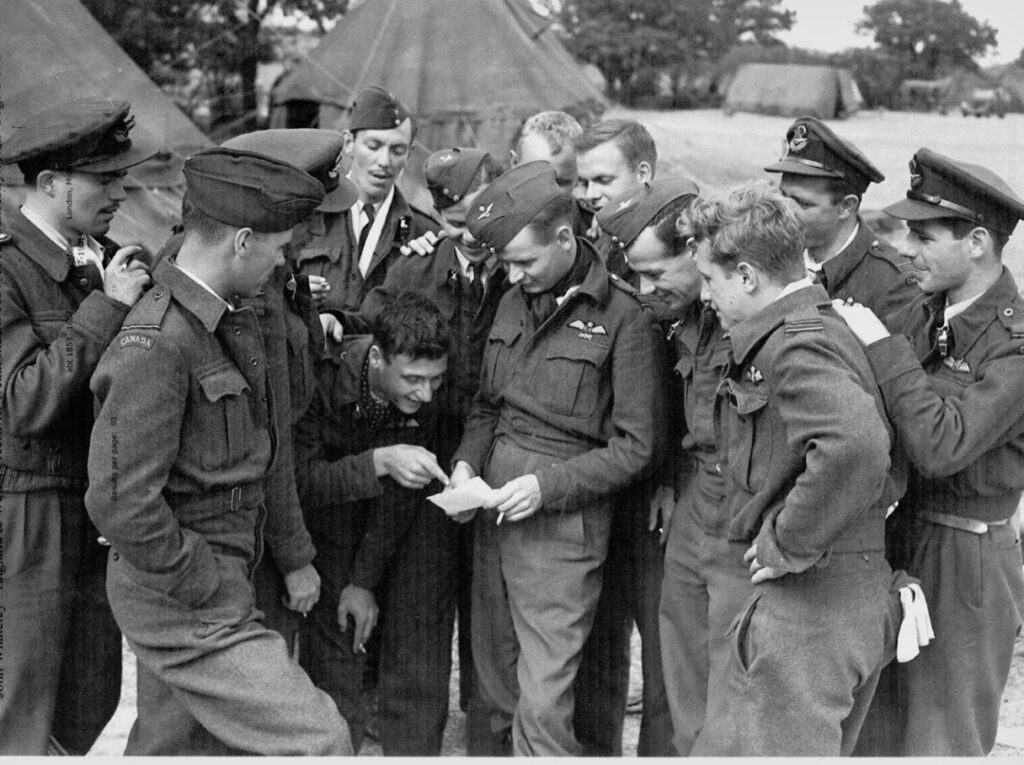

The 414th RCAF (Royal Canadian Air Force) Squadron, who were at Ashford from August to October 1943 (alongside the 430th), and its Squadron Leader, ‘Herb’ Peters, feature heavily in the photographic evidence of life at RAF Ashford for the RCAF.

From his photo archive, shared with us by his daughter Esther Jones, we can see just how minimal the living conditions were for most men: most were using tented accommodation, with many daily tasks performed outdoors.

However isolated the airstrip may have felt, being situated in the middle of swathes of uninhabited agricultural land at that time, RAF Ashford was still an entirely functional airbase, with modern communications – which meant the occasional letter from home!

The flying men of the RCAF, however dapper they appear wearing shirtsleeves and ties even while camping, were still not immune to the risks involved in their regular operations flying into France: we can see here the evidence of an unfortunate (although reportedly not lethal) crash landing at Ashford by the 414th.

Taken at other ALGs, photos in the Imperial War Museum archive show what may have felt a bizarre, surreal experience of flying, maintaining or supplying the cutting-edge aeronautic engineering of fighter planes, while living in the most basic of lodgings.

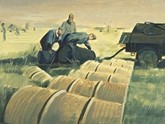

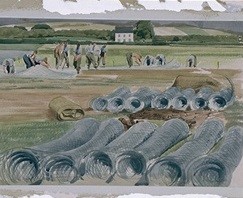

Among the duties taken up by personnel at RAF Ashford was the repetitive and exhausting task of manually laying out Sommerfeld tracking.

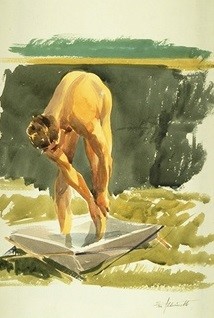

Illustrated by British-born Canadian war artist, Eric Aldwinckle, one of the RCAF personnel at the airbase, this job that would become in setting up the necessary infrastructure for Allied air forces to land further into Europe, was such a familiar sight that it appears in multiple paintings.

Although Aldwinckle did produce paintings on a number of subjects while at RAF Ashford, such as Mustangs at Readiness (above), one can imagine how familiar a sight it must have been to see personnel rolling out of the landing track at the airbase, especially considering that this task is one of the few duties he illustrated as they were being performed. These ‘magic carpets’

USAAF

USAAF were the second main users of the Airfield, camping out there between April to the end of July 1944, represented by the 406th Group of 512th, 513th, and 514th Squadrons [Photo: 512 colour photo][i]

[i] Delve, K. (2005) Military Airfields of Southern Britain – Southern England

Of the Flying Group, our research has uncovered more documentary evidence on the 512th than the other squadrons from the USAAF at Ashford:

What were the Americans’ first impressions of Ashford/?

In “The Official History of the 512th”, published in 1981 as an abridged version of the original 512th Fighter squadron history, it is reported that the 512th arrived at RAF Ashford, following an advanced party, on the 6th of April 1944, remarking that “we were taken out to our airdrome which was throbbing with mud”, and that the “Squadron area is a large square surrounded on all sides by a natural hedge and trees. The tents are dispersed around this hedge”.

The pilots, in this report, awaited the delivery of their Mustangs, which, on arrival, they immediately began to undertake training missions. 307 hours of training in formation flying and dive bombing were completed just by the 512nd from RAF Ashford across its 17 planes.

Further into May, the 512th are reported here to have completed nineteen total non-training operations flying to and from France and Germany, escorting larger bombers or, in one case, bombing a railway bridge, glibly referred to by the Squadron as “geography lessons.”

Being mere weeks from D-Day, it would be at Ashford that the final details of this Flight Group’s part in the operation were ironed out by its own Intelligence Officers, with more instruction given by the 303rd Wing.

On the 24th of May, the squadron made a trial movement en masse to a nearby Advanced Landing Ground, at Brenzett, practising relocating a whole squadron to the ALGs they hoped to be built in Europe, which was an apparently successful dry run.

In their “Official History”, June was reportedly “a month of intensified activity”.

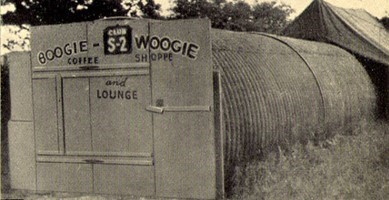

From the 514th we have an annotated and illustrated booklet featuring much of the daily life of the American airmen at Ashford, which show that camping life was entirely liveable despite the “throbbing” mudscape, if one eventually found a good position in which to shave (above), and or created a pop-up ‘speakeasy’, such as their mobile, corrugated iron “Boogie Woogie, Coffee Shoppe and Lounge”.

Issues regarding transporting personnel across the wide plane on which the two landing strips of RAF Ashford were mapped appears to have been solved by use of military vehicles outside their approved passenger numbers (below).

The Remembrance Tree

It should be remarked on, however, that for some men at RAF Ashford, this was not a site merely of camping and camaraderie: this was a site where men would see their comrades take to the air and never return.

In 2014, Bernie Sledzik, USAAF 514th, from Altoona, Pennsylvania, visited the site of the airfield at RAF Ashford and was able to identify an oak tree that had operated as a site to remember fallen friends, and where he himself had been found weeping, believing his close friend, missing after a completed mission, had died.

Lieutenant E. Springer, Bernie’s friend, had, in fact, been safely harboured by the French resistance for several weeks after a safe landing in France, and would return to fight with the 514th.

After the RCAF had left RAF Ashford, Squadron Leader Herb Peters would die, at age 25, in 1943. Bernie would go on to fly 67 missions over Europe. The tree still stands in its original location.

RAF Ashford and D-Day

It should be remembered that the raison d’être of RAF Ashford, its temporary nature, its ability to be constructed then deconstructed, and the continuous practising of rolling out and rolling up Sommerfeld tracking by those stationed there, was to train Allied forces ahead of the invasion of occupied Europe, which would begin on D-Day.

Before being shot down over Luxembourg (alive but with heavily singed eyebrows), a then 19-year-old Malcolm McLane, of New Hampshire, flew 73 combat missions, many out of RAF Ashford, from whence he flew out for D-Day (6th of June 1944).

For McLane, like many others, even the smallest of memories from that day: the clatter of mess tins, your single egg at breakfast, are burned to memory.

In an interview with his local paper in Concord, New Hampshire in 2004, McLane wrote on the frenetic atmosphere of that mission, watching the invasion from afar after a pre-dawn take-off at 3am.[i]

“It’s three o’clock, Tuesday morning, June 6, 1944. Someone is shaking you in your blanket roll, but you’re too sleepy to get up, for you didn’t get to bed until midnight and it was after one before the talking quieted down and you got to sleep. Then the bright light goes on in your face, and you remember what you were told in that three-hour-long, secret briefing last night: “Today is D-Day!” You tumble out as best you can, put on extra socks and heavy shoes from force of habit, for someday you may have to walk back. There’s some hot coffee and an egg in the mess tent, then you pile into jeeps and trucks and hurry to the line, where the ground crews have already been warming up the planes. Malcolm McLane in Army Air Force. There’s your Mae West to put on, your helmet and goggles and chute to put in the plane, before you pack into the squadron briefing tent and get courses and instructions regarding your mission. There’s no comment on the weather, as there usually is, for it’s obviously terrible. Ordinarily the mission would be scratched, but there’s no canceling this one. Fifteen minutes before start-engine time, you’re in your plane checking everything and getting buckled in. It’s still dark, for the sun isn’t due to rise for over an hour and there won’t be much twilight with this solid overcast and misty rain with its low ceiling and visibility. Belly tanks cause some trouble as you taxi out, but there’s no waiting for stragglers. Those who can make it are off the ground and circling over the field, trying to get into formation. It’s no easy thing, and many wander home alone. Once you’ve set course, you must climb up through the overcast on instruments. The formation breaks up even more, and when you break out on top, headed into a full moon and a clear sky, you find yourself alone on your element leader’s wing. The rest have popped up through the blanket of clouds on their own and are doing their best to find the patrol area separately. Navigation is a matter of compass headings and timing, for there are no landmarks here over this ocean of white. To the east the sky gets lighter all the time. After an hour occasional breaks appear below, and the two of you spiral down to reconnoitre. It’s France all right, but where? A radio call and a fix, and soon you’re given a heading to target. Below the clouds it’s murky again, but the light behind you is getting pinker and the fleecy clouds at the bottom of the overcast are a lovely soft red. Below, ships begin to appear, their guns flashing in the darkness, while the rising sun brings out their forms gradually and makes the water a deep red. The air is still misty and the visibility poor, but this only adds to the sun’s reddish glare. For another hour you patrol back and forth over the beachhead-to-be as the big guns pound away. And then when you’re about to leave – your gas is getting low – a little fleet of boats leaves the great fleet offshore, passes the outermost ring of destroyers and heads for the beaches. As you head back across the channel to England, the scattered small wakes of the landing craft move toward the shore. In another few minutes the invasion will have begun. More planes will relieve you, and many more ships will follow those first boats, but that hour before H-hour will be a never-forgotten memory of this war, whose other details I will willingly forget. My part was nil, for there was no opposition from the air, but our mission was carried out and the beachhead won.”

D-Day, or, its success, would mark the beginning of the end of RAF Ashford as an airfield – the 512th Squadron was reportedly among the first flying groups to reach the Normandy beaches on the 6th of June, and by the 5th of July (one hopes these American pilots had not celebrated too much the previous day), they were ordered to proceed in moving wholesale to a new base in France with all their equipment, such was the success of the Allied advance.

Further, the well-practised swift (but no doubt laborious) installation of Sommerfeld tracking would become instrumental in constructing not only new ALGs in the continent, but in laying road networks at speeds to match the rate of advance.

Eventually, the 406th’s mobile Boogie Woogie Lounge would reach Germany, then renamed the “Kaffee Haus und Lounge”.

From the earthy delights of shaving outside a tent, to the task of flying dawn patrols into the unknown, the lives of men who passed through RAF Ashford left almost no trace on the landscape, but they can be remembered by a single tree.

[i] Brooks, R. J. (1998) Kent Airfields in the Second World War

[ii] Delve, K. (2005) Military Airfields of Southern Britain – Southern England [iii] Copyright (c) Concord Monitor, 2004